Developed by neurobiologists Kamila and Henry Markram (2010), the Intense World Theory of Autism sheds a new light on autistic being-in-the-world, despite not avoiding pathologising rhetoric.

Based on neurological experiments, the Intense World Theory demonstrates hyper-reactivity and hyper-plasticity of local neural microcircuits in autistics, translating into hyper-perception, hyper-attention, hyper-memory, and hyper-emotionality. With this observation, the theory switches from the deficit rhetoric to a logic of intensity. In this sense, it echoes the recently popularised figure of the empath and gives it empirical support. Besides, the theory claims to offer a unifying view of autism, explaining all autistic traits rather than only a few.

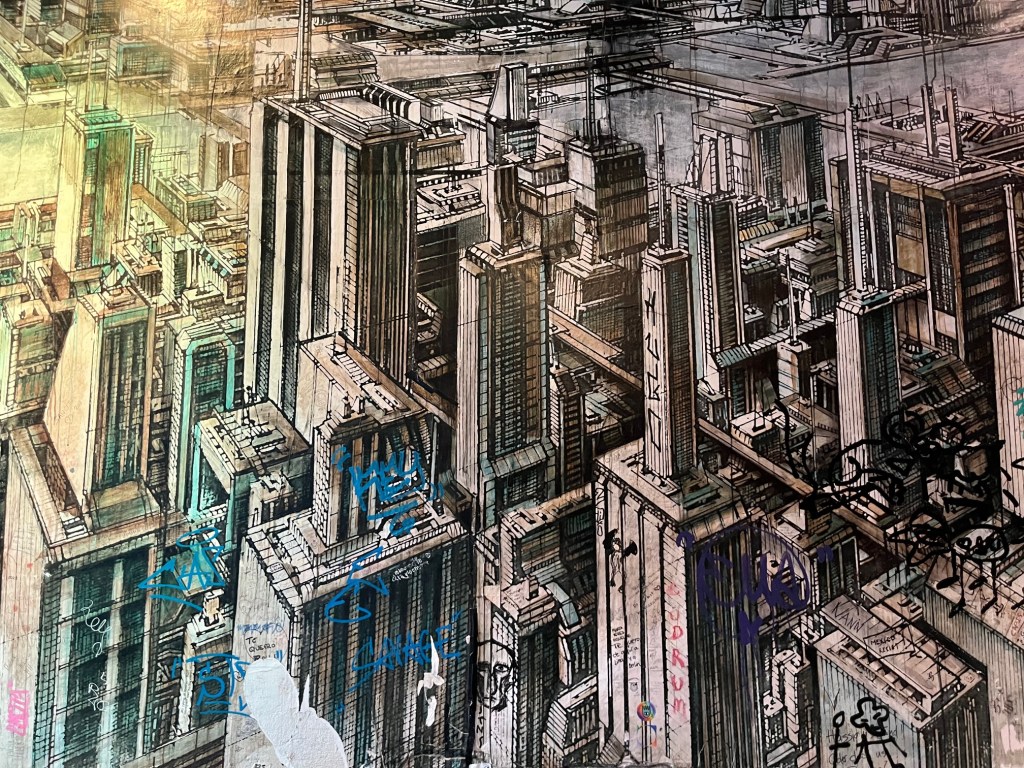

For these reasons, the theory has been mostly well received by the autistic community. With its insight, we get a confirmation that autistic people are not fundamentally disconnected and solitary, but rather hyperconnected and hypersensitive. Consequently, we tend to perceive the world more intensely, and sometimes, too intensely. Because of this, we experience what the Markrams call ‘ the ‘“intense world” reaction’ (2010: 19), which leads us to withdraw from the intense world to our personal bubbles.

In the Intense World Theory, autistic disconnection, withdrawal, or asociality (however we call it) is not a fundamental and core symptom of autism but a protective response to an unbearable social and material environment. This is even more understandable in our modern globalised world, characterised by fast-paced, high-intensity stimulation (both cognitive and sensory). It is not that autistic people exist outside of the world, but that we are in it so intensely that we sometimes need to escape it for a minute – to hide in our bubbles.

To prevent embodied responses like shutdown, the Intense World Theory calls for more compassion for autistic children, who should not be forced to live in unpleasant environments but allowed to enjoy toned-down ones. However, the Markrams make use of pathologising language and call for the prevention not only of the ‘intense world reaction’ but of autism itself.

Curiously enough, they seem to distinguish between autistic hyper- traits (hyper-attention, hyper-memory, and so on) and autism itself, viewed as a pathological reaction to the intense world. This distinction is fuelled by a rather sexist and Aspie supremacist perspective which values autistics only insofar as we can make beneficial contributions to society as world-leading scientists or CEOs. Autistic hypersensitivity is embraced only to the extent that it can be made hyper-productive, and the Markrams argue that the intensity of autistic withdrawal is proportional to potential genius. In this sense, Henry bases his own entrepreneurial ethos on his own autistic traits but never acknowledges his autism per se.

As such, while it was developed by an autistic person, the Intense World Theory does not fully embrace the neurodiversity paradigm. Though it brings forth a more dynamic and compassionate understanding of autism, its Aspie supremacist bias brings pathologisation back into the picture. By engaging with it critically, we can still learn a meaningful lesson about autistic being-in-the-world in general, and autistic ‘bubbles’ in particular.

Reference

Markram, Kamila and Henry Markram. 2010. The Intense World Theory – A Unifying Theory Of The Neurobiology Of Autism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 4(224): 1-29.

This blog post is based on a forthcoming publication, ‘A Foray into the Bubbles ot Autistics: The Phenomenology of Being-in-the-world from Umwelt Theory to Intense World Theory’ for Minority Reports: Cultural Disability Studies (2025).

Leave a comment